18/06/20

4 min read

From the start of the pandemic it has been clear that this was going to be more than just a public health crisis. COVID-19 has both accelerated and dramatised some of the most urgent social, economic and technological trends and stress points in our society, challenging institutional structures and forcing governments to account to their citizens in an unforgiving international context.

At the heart of the pandemic and its implications has been the question of public trust – the relationship between consent and authority, self-interest and solidarity. Trust in the handling of the pandemic has been grounded in the interpretation of epidemiological data, “following the science”, and in wider questions about inequalities of risk, suffering, intergenerational equity and long-term outcomes.

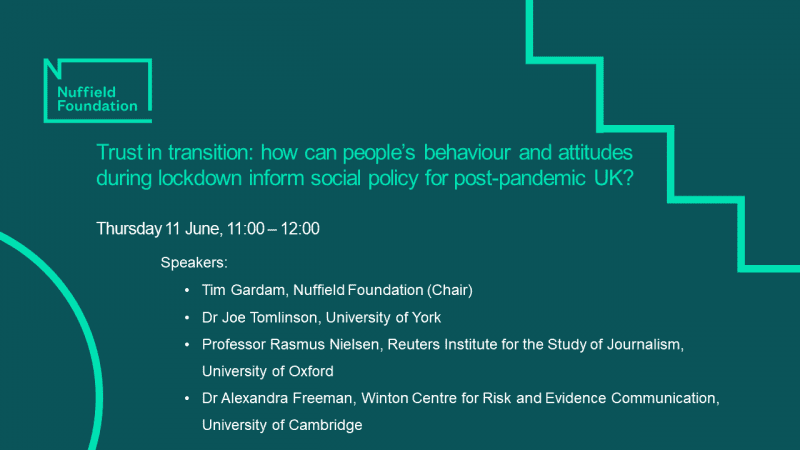

At a recent Nuffield Foundation webinar, Trust in Transition, three research projects brought many of these issues together. The Foundation has committed over £2m to research projects that are charting the social, educational and economic effects of the pandemic as it develops. The first waves of research reveal quite dramatic shifts in public sentiment and behaviours over the course of the first weeks of the pandemic; they give a foretaste of the enduring volatility of our social contract and the uncertainties of what will follow.

Emerging trends in compliance and trust

Boris Johnson is quoted as saying he has learnt that it is much easier to take people’s freedoms away than to give them back. Joe Tomlinson, from York Law School, has explored how people view the trade-offs between their individual rights and the greater good; he has identified why there were initially such high levels of compliance with the draconian restrictions on personal freedom – where concern for family was more than matched by a sense of public solidarity with the NHS; but he questions how resilient this will prove to be.

Rasmus Nielsen from the Reuters Institute at the University of Oxford and Alex Freeman from the Winton Centre at the University of Cambridge charted the interaction between trust in government, media and scientists. The Reuters research suggests the speed of the decline of trust in government competence in the UK has been unprecedented; (trust in news organisations has also declined but at a lesser rate). As the virus progressed, what Rasmus Nielsen called the initial “rally round the flag – we are all in it together” public response has given way to a realisation that the virus’ effects have been far from equal – most devastating in the most socially disadvantaged areas of the UK and among some minority ethnic groups. As in the Brexit and election debates about “levelling up” and “the left behind”, geography has again proved its significance in British society.

The international picture

However, what has made the pandemic different is the way it has unusually, in the grim league tables of comparative mortality rates, forced international comparisons to the fore of the UK debate. The most striking aspect of Alex Freeman’s survey across 11 countries in Europe, North and South America, China and Asia, was its demonstration of how different are some cultural determinants of public trust. Her qualitative research gives a voice to the data. Japan is the unlikely outlier in having generally lower levels of public trust, revealing a vituperative public disdain for government – “a group of idiots”, “I hope the Prime Minister dies of the virus” – and uniquely high levels of distrust in the WHO due to perceptions of its association with Chinese influence. Germany’s success in handling the pandemic correlates with it having high levels of public understanding of the official messaging. In the UK, though we may comfort ourselves that we have avoided the visceral public health politics fomented by the White House that have so disfigured the US debate, Rasmus Nielsen also produced sobering survey data that suggests that, in the UK too, there has been a deeply partisan divide on Left/Right lines regarding government handling of the virus.

“Following the science”

What most worried the researchers? For Alex Freeman, it was a growing sense that trust in “official science” may also be eroding. Joe Tomlinson identified our preparedness to comply as likely depending on a belief in both the competence and the transparency of governmental authority. He enumerated those factors that risk undermining the delicate accommodation reached initially in the face of the extremity of the virus – ineffectiveness of the rules, other people not complying, unacceptable rights violations, over enforcement, procedural unfairness. Most of these shortcomings will be laid at the door of government, but when government defends itself by claiming that its authority derives from “following the science”, then there must be a risk that the independent evidence the epidemiologists provide can itself appear compromised. As Rasmus Nielsen observed, this problem may be compounded by our desire to see science as definitive, when in fact research science is defined by uncertainty. In this sense, medical science may be about to face the scepticism of experts that has eroded trust in other evidence-based policy in recent years.

Yet, as Rasmus Nielsen concluded, healthy democratic scepticism may be a strength. Rather this than some of the responses in Alex Freemans’s survey of Chinese opinion where trust in social media appears to be greater than elsewhere because, as it was regulated by government, it must be right. As one respondent put it – “Believe in the country, support the country, co-operate with the country”. Elsewhere it is not quite that simple – but as Alex Freeman’s research concludes, people follow advice they trust.

About the author

Prior to joining the Nuffield Foundation in September 2016, Tim was Principal of St Anne’s College at the University of Oxford, a post he held for 12 years. He is also Chairman of the Which? Council.

Tim worked for 25 years in senior broadcasting roles, starting at the BBC where he was editor of Panorama and Newsnight, and later becoming Head of Current Affairs and Weekly News. He was Director of Television and Director of Programmes at Channel 4 from 1998 to 2003. From 2008 to 2015 Tim was a member of the Ofcom Board and was Chair of the Ofcom Content Board.

Tim was also the author of the Department for Culture Media and Sport Review of BBC Digital Radio Services in 2004, a member of Lord Burns’ Advisory Panel on the BBC Charter Review and a Director of SMG plc from 2005-7.