20/10/21

5 min read

Almost all children attend nurseries or childminders well before they start school, but despite significant public funding, there are inequalities of access and take-up, particularly for disadvantaged children. Services remain prohibitively expensive for some parents while being provided by a workforce that is poorly paid and undervalued.

A new report published today by the Nuffield Foundation reviews the evidence on the quality, effectiveness and sustainability of early childhood education and care. The sector has grown exponentially over the last 25 years, from limited provision in the mid-1990s to an established UK-wide infrastructure. But this expansion has been piecemeal, as policy implemented by successive governments has prioritised different objectives at different times. Some polices have sought to support child development and learning through early education, others to reduce gaps in attainment between advantaged and disadvantaged children, and some to increase parental employment through access to flexible and affordable childcare. In practice, this has led to a complex and confusing system that is failing to meet any of these objectives as fairly or comprehensively as it should.

The report, The role of early childhood education and care in shaping life chances, calls for a whole-system review of early childhood education and care, to inform a new strategy designed to deliver quality of provision for children, affordability for parents, improved training and pay for the workforce, and which makes a particular difference to the lives of disadvantaged children.

A mixed market of provision and funding that is confusing for parents

In 2019 there were over 1.6 million registered early education and care places, of which almost half (47%) were in private nurseries, 20% in state-maintained schools, 18% in the voluntary sector, and 15% provided by childminders. Government funding in England amounts to £5.7 billion a year, including Sure Start, and is split between free entitlements that go directly to providers, and support for parents to reduce the cost of childcare through the benefit system or tax-free childcare and employer childcare vouchers.

However, real term spending per hour for places fell by 9% between 2018/19 and 2019/20 and government funding is not meeting the true cost of provision of funded places. The funding rate given to local authorities in England is two thirds of what the government predicted would be needed to fully fund the free entitlements. This shortfall is having a detrimental effect on the sustainability of providers, particularly in more deprived areas – 35% of nursery closures in 2018 were in areas in the 30% most deprived wards in England. This has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has meant reduced attendance and therefore reduced income for providers.

Conversely, funds such as the Tax-Free Childcare scheme are underutilised – in the past three years the government spent £385 million on tax-free childcare, compared to its initial forecast of £2.1 billion. The complexity of multiple entitlements with different eligibility criteria and the ways in which these are implemented locally can be confusing for parents whose access to childcare is dependent on where they live, the services their children need and what they can afford.

Demand is high but take-up is lower for disadvantaged children

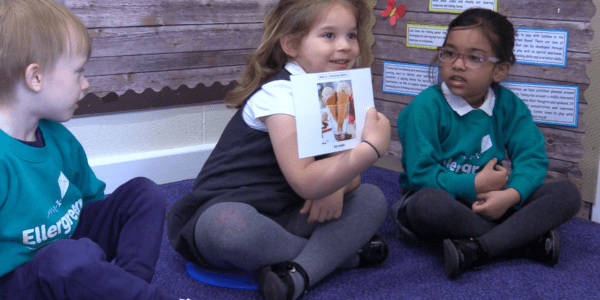

Demand for early childhood education and care is high – 93% of three- and four-year-olds accessed their 15 funded hours a week in 2019 – but there are inequalities in take-up and gaps in provision. The most disadvantaged three- and four-year-olds are least likely to access their funded entitlements and take up is also lower among children from some ethnic minority backgrounds, and among children with English as an additional language. Children with Special Educational Needs or Disabilities(SEND)often have difficulty accessing their full 15‑hour entitlement, or any early education at all. There is a major gap in provision for children under the age of two.

Take-up of the two-year-old funded entitlement for disadvantaged children is relatively high, but lower than policy targets and highly variable across the country—ranging from 39% to 97%. On average, close to one in three disadvantaged two-year-olds are missing out, a problem compounded by the reduction in Sure Start services, which have been shown to improve health outcomes and emotional and behavioural development of children. This is of particular concern given that the gap in the proportion of children assessed as having a ‘good level of development’ when they start school is 17.8 percentage points lower for disadvantaged children than their peers, and has been marginally increasing since 2018, having previously been narrowing.

Early education and childcare can help address this gap, particularly when quality is high and provision is accessed at a young age and for a sustained period, although some of these effects may not last through primary school. The home learning environment also plays a vital role in children’s overall development. Addressing gaps in development is more important than ever, as early indications show children starting school since the pandemic have fallen behind in relation to their learning and personal and social development.

In recent years, public funding has increasingly moved in the direction of expanding childcare for the benefit of working parents and away from the earlier emphasis on ‘early education’. The 30 hour policy increases the amount of funded hours for children whose parents work more than 16 hours a week, but concerns have been raised that the policy is inadvertently accentuating disadvantage, as in practice, it means the most disadvantaged children receive less early education. By contrast, Scotland has extended its 30 hour free childcare offer to all three- and four-year-olds and eligible two-year-olds.

An underpaid and undervalued workforce

Recognition of the value of early childhood education and care is not matched by the rewards for those working in the system, who are predominantly young and female – one third of staff in nurseries are aged 18-20. The average wage in the sector was £7.42 an hour in 2018, compared to £11.37 an hour across the female workforce and in 2019, 45% of childcare workers were claiming state benefits or tax credits. Turnover of staff is also increasing, rising from 13% in England in 2013 to 24% in 2018.

There is a strong relationship between the level of staff qualifications and the quality of early childhood education and care, but despite cumulative reforms, qualification levels vary across the sector and the childcare workforce is less qualified than both the teaching workforce and the general female workforce. Staff in schools are more highly qualified than those working for private, voluntary or independent nurseries, where there has been a decline in the proportion of staff with an NVQ level 3 from 83% in 2015/16 to 52% in 2018/19.

Carey Oppenheim, Early Childhood Lead at the Nuffield Foundation and co-author of the report said:

“We have moved from very limited provision of early childhood education and care in the mid-1990s to the current situation where the vast majority of children under five attend some formal provision. This is a remarkable shift that has seen the development of a nationwide infrastructure on which many children and parents depend, but the system is dysfunctional. It is not working for children in terms of quality of provision, for parents in terms of access and affordability, for the workforce on pay and training, or for providers on sustainability.

“We need a wholesale review of the purpose and provision of early childhood education and care that provides clarity on who and what it is for and how it can make a difference to disadvantaged children in particular. Such a review also needs to consider the fairest and most sustainable funding model and how the people providing care can be appropriately skilled and remunerated.”

Read the full report