Dr Tim Bateman, Visiting Academic Consultant at the University of Bedfordshire, is researching why children from minority ethnic backgrounds are over-represented in the youth justice system (YJS) in comparison to white children.

Tell us about your Nuffield-funded project

The project aims to explore decision-making at what is sometimes called the gateway to the youth justice system (YJS) – the point where decisions are made about which children should be prosecuted, given a caution, or diverted to an informal outcome which doesn’t lead to a criminal record. In particular, we are aiming to identify if – and in what ways – decisions vary for children from different ethnic backgrounds.

What were the origins of the project?

Responses to children who break the law have changed dramatically over the last decade. There is growing recognition that entering the YJS is often counterproductive because it increases the risk of reoffending and can lead to a range of other poor outcomes. This has led to a rapid expansion in the use of informal diversionary mechanisms, including: community resolution, a diversionary police outcome frequently involving a restorative element; and Outcome 20 and 22 which can be recorded by the police as ‘no further action’ where a referral for intervention has been made to another agency. The introduction of such measures has coincided with a reduction of around 80% in the number of children who receive a formal youth justice sanction.

However, these largely positive developments have been accompanied by worsening over-representation of children from ethnic minority backgrounds within the YJS. This appears to be because there has been a larger decrease in the numbers of white children entering the YJS.

Little is currently known about how decisions are made about who should benefit from diversion to informal outcomes, or what happens to those children. There are no published data on diversionary outcomes or the characteristics of the children. The research team is aiming to provide evidence to explain why ethnic disproportionality within youth justice has increased, and to develop practical recommendations that might address what is generally acknowledged to be a major shortcoming of youth justice provision in England and Wales.

Why does this research matter?

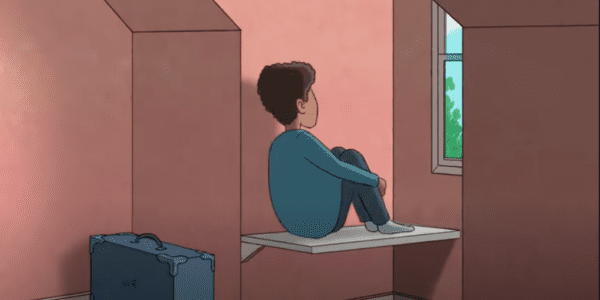

Concern about over-representation of minority ethnic communities within the criminal justice system is decades old but in spite of extensive research and considerable policy attention, little headway has been made in reducing disparities. More than five years ago, David Lammy MP, in his government-commissioned review on the treatment of minority ethnic people within the criminal justice system, identified the YJS as his ‘biggest concern’. The implications for children from minority backgrounds are considerable. The legacy of a criminal record restricts life chances and frequently initiates a process of labelling which has long-term impacts. Awareness of differential treatment also undermines trust among children from minority communities in the criminal justice system.

Understanding how decisions made early in the YJS influence later disparities, is key to developing processes that ensure vulnerable children are treated equitably.

The legacy of a criminal record restricts life chances and frequently initiates a process of labelling which has long-term impacts.

What motivates your research interests?

My whole career has been focused on youth justice. For many years I was a social worker supporting children in trouble, but I became increasingly disillusioned with how the system responds to this particularly vulnerable and disadvantaged group. I moved into youth justice policy, developing a critique of existing arrangements and promoting more progressive, child-focused practice. I started to work on research that would help to illuminate the policy areas I wanted to focus on and then moved into full-time academia.

Can you tell us about the project team and how you all work together?

The project team is based, for the most part, at the University of Bedfordshire and comprises colleagues who have worked together closely on an array of previous studies. The team includes one colleague from Keele University who played a central role in a previous research project, funded by the Nuffield Foundation.

What’s your experience of being funded by the Nuffield Foundation?

I’ve found the Foundation very easy to work with and a flexible funder. They have a real interest in what can be learned from the research and how it can have impact. But they also recognise that research is a messy business that throws up a range of unanticipated obstacles that need to be negotiated.

What are you most proud of having achieved in your career or professional life to date?

Retaining a belief in the power of research to make a difference.

Read more about this project

The Nuffield Foundation is an independent funder. The views expressed by Nuffield-funded grant holders are not necessarily those of the Foundation itself.