13/05/20

2 min read

Children starting primary school may benefit from a new approach to teaching reading, that fully integrates phonics and language teaching, according to new Nuffield-funded study from City, University of London.

Learning to read is a complex process involving phonics skills and language skills. Phonics involves teaching letter-sound correspondences and awareness of phonemes (sound units), and language skills include vocabulary, grammatical knowledge, and comprehension.

Current educational practice focuses on phonics with less emphasis on language. Although many children progress with a phonics approach, a significant proportion struggle, particularly those with weak language skills. These include children from disadvantaged backgrounds, children with English as an additional language, and those with language difficulties, of whom deaf children form a significant group and one that is typically excluded from reading intervention research.

Two groups of children at risk for poor reading took part in the study: disadvantaged hearing children in mainstream schools and deaf children in hearing impairment resource bases. The schools were located within the lower 10% to 50% of the most deprived neighbourhoods in the UK. There were 138 children (77 boys, 61 girls) of whom 23 were deaf, with an average (mean) age of 4.9 years. Children were tested at the start and end of the school year to assess their reading, spelling, phonological (speech sound related) and language abilities.

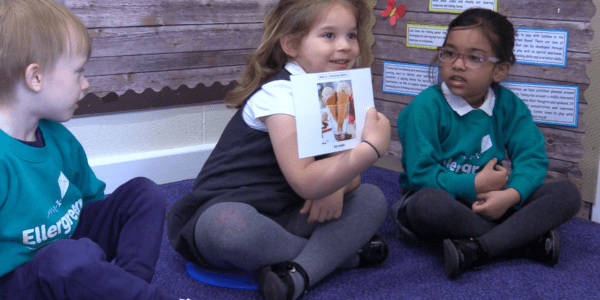

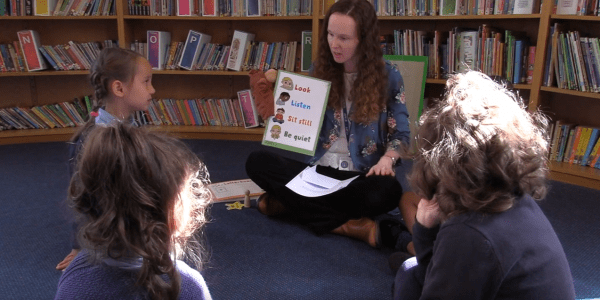

The integrated programme combined two practitioner-developed programmes that target the components of reading in a complementary way: ‘Floppy’s Phonics Sounds and Letters’ for developing phonics skills and ‘Word Aware’ to develop language skills.

The study suggests that children who received the integrated programme made significantly more progress on key outcome measures of single word reading and spelling at the end of the study in comparison with the control group who received the standard literary teaching in schools. Analyses of some measures presented mixed findings, in part because many of the children could not manage these tests, even though they are used widely with this age group. In addition, the integrated programme was found to be feasible and acceptable for teachers to deliver in both study settings.

Rosalind Herman, Professor of Child Language and Deafness at City, University of London said:

“Very low levels of reading ability meant that some of our original tests were not feasible to use with all the children involved in our research. This highlights the challenges disadvantaged and deaf children face when learning to read, and the need for new approaches such as our integrated programme to give them the best start in life and education.

“We’ve learned valuable lessons from this pilot study and look forward to developing the full trial to answer important questions that could help these children and their families.”