23/03/21

5 min read

Incidents of serious harm to children under five where abuse or neglect is known or suspected increased during the early months of the pandemic, and many other children at risk may have been missed due to disruption in the usual pathways for referring children to services.

Children’s services are already under pressure as a result of increasing rates of child protection interventions over the last decade, particularly for children living in the poorest areas. In the same period, preventative services to support families have been cut, and many young children who are at risk of abuse or neglect do not come to the attention of services at all.

These findings are highlighted and explored in a new Nuffield Foundation evidence review that draws on over 140 sources to shed light on changing patterns of abuse and neglect in early childhood in England and Wales over the last 20 years. The review, Protecting young children at risk of abuse and neglect, calls for urgent re-evaluation of the current system, with a focus on how public services and agencies can adopt a holistic and collaborative approach to support young children at risk of abuse and neglect, prevent harm, and promote positive outcomes. The time is right for such a re-evaluation, given the current independent review of children’s services, commissioned by the government as ‘a once-in-a-generation opportunity to reform systems and services.’

The impact of COVID-19

Incidents involving death or serious harm to children under five where abuse or neglect is known or suspected increased during the early months of the pandemic (April to September 2020). Compared to the same period in 2019, such incidents increased by 31% for children under one (a total of 102 children) and 50% for children aged one to five (a total of 48 children). The average rate of increase for children across all age groups was 27% (a total of 285 children).

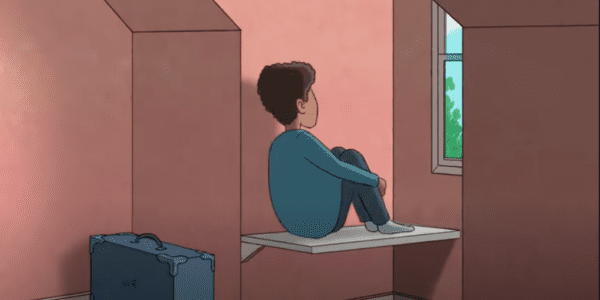

In addition, the pandemic has disrupted the usual pathways for referring children to services, meaning children at risk of abuse and neglect may be being missed. These issues appear to be even more acute for infants and for babies born in the pandemic, with many children’s centres closing and health and GP check-ups coming via video link or telephone. For example, in some areas of the country up to 50% of health visitors in England were redeployed during the first 2020 lockdown, with only one in ten parents of children under two seeing a health visitor face-to-face.

This is particularly worrying given that even prior to the pandemic, a considerable number of young children at risk due to their family circumstances are missed by services each year. In 2019, 46% of children who died or were seriously harmed in 2019 were not known to the child welfare system. It is estimated that there are over half a million children under five (17%) living in a household with domestic abuse, parental mental health problems or parental substance misuse.

Long-term increases in children taken into care

An increasing proportion of young children have been subject to child welfare interventions over the last 10-15 years. The proportion of babies under one year old subject to care proceedings in England increased from 51 to 81 per 10,000 children between 2008 and 2016. For babies under one week old, the rate more than doubled (from 15 to 35 per 10,000 children).

During this time, spending on preventative services to support families who are under pressure and struggling in England has fallen from £3.8 billion in 2010 to £2.1 billion in 2018 (reductions have less severe in Wales), while spending on statutory and acute services, such as provision for children in care has largely been protected. This is at odds with evidence that shows interventions at the right time in early childhood can protect children and support their families to help them thrive, particularly when offered as a holistic, ongoing package of support across different children’s and adult services.

A lack of data makes it impossible to ascertain fully the extent to which the increases in child protection and welfare interventions are because of actual increases in abuse and neglect, more reporting, more risk-averse social work or cuts to preventative services. In all likelihood it is a combination of all these. However, there is evidence that the chance of experiencing a child welfare intervention is not experienced equally across all families and that poverty is a driving factor. Children living in the poorest neighbourhoods are at least ten times more likely to be in care than children in the richest neighbourhoods, and this relationship is stronger for pre-school children. There are also inequalities between ethnic groups in the proportions of children being looked after in England, although little attention has been paid to these inequalities by policy makers and there is a lack of evidence to sufficiently understand and explain them.

A natural consequence of blunt data, and variable practice and thresholds, is that two children can have similar levels of need, but one will be in care and the other will not. Conversely, two children in care who appear to be similar from the data can actually have very different lives and needs. The review concludes that the ongoing debate about whether too many or too few children are taken into state protection is not only impossible to answer given the inadequate data available, but is the wrong question to be posing. Instead, attention needs to be given to whether public services are intervening in the right way to prevent harm and promote positive outcomes for young children.

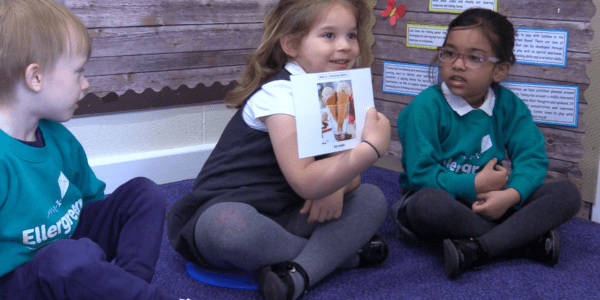

Outcomes for children

Young children subject to child welfare interventions have poorer early language development and this gap persists as they start school. Children who are (or have been) in care score 24% lower in English, maths and science at Key Stage 1 (aged 7) than children who have not received a social work intervention. For those who have ever had a Child in Need Plan, these scores are 14% lower. Opportunities to address these gaps are being missed because too many children do not take up early education places. There is no national data on how many looked after children access early education, but analysis of selected local authority data suggests that amongst looked after children aged 2-4, 71% are in early education compared to a national average of 85%.

Carey Oppenheim, co-author of the review and Early Childhood Lead at the Nuffield Foundation said:

“The independent review of children’s social care services currently underway is recognition that our system of child protection and support needs to be re-evaluated. Over time, we have seen a shift away from provision of early support to help families who are struggling, towards later interventions that are more likely to separate families and which are more expensive to provide. Alongside this, there are young children at risk of abuse and neglect who need help and are not receiving it because they are not known to services. These concerns have been pulled into sharper focus by the pandemic, and its economic consequences are likely to mean more pressure on council budgets and services at exactly the point families need them most.

“At the same time, we cannot solve all the problems faced by young children through children’s social care services – social work and family justice are only one part of the solution. Poverty remains a significant risk factor for children and alleviating the financial pressure on families would make a difference in enabling young children to thrive, as would a more holistic and collaborative approach across public services and agencies.”

Download evidence review