26/05/22

3 min read

Pressures on many parents of young children have been increasing over the last 20 years and have intensified during the pandemic. Some of these pressures are financial and will be increased further by the cost of living crisis, putting young children’s well-being and development at risk.

A report published today by the Nuffield Foundation reviews the evidence on the changing nature of parenting children under five. It finds that parents are increasingly under pressure as a result of expectations, a lack of time, the balance of paid employment and providing care for young children, poverty, and inadequate housing. All of these factors can affect the care parents provide and children’s development and well-being.

The report also finds that some parenting programmes can improve parenting skills and outcomes for children, but such programmes are less likely to succeed if not combined with action to reduce pressure on families, such as improving household incomes.

The report brings together research from over 100 studies to show how the different pressures facing parents of young children compound and can impact young children’s development.

Increasing rates of poverty and poor housing

Even before the cost of living crisis, more than one in three (36%) children in families with a child under five in the UK were living in poverty. Poverty can have a direct effect on children’s outcomes through constraints on parents’ ability to afford the basics such as food and housing. It can also create parental stress, depression and conflict between parents, which may impede effective parenting and, in turn, affect child outcomes.

One in four children now start school while living in privately rented housing. With the highest rates of non-decent housing, privately rented housing is over five times more likely to be over-crowded than owner-occupied housing. Features of low-quality housing, such as overcrowding, damp and problems with heating may significantly affect parents’ and children’s lives. Privately rented housing is also less secure, which puts children at increased risk of needing to move school and away from family and social networks.

There are also significant inequalities among ethnic groups in relation to overcrowding. Almost one in four (24%) of Bangladeshi British households are overcrowded, compared to just 2% of White British households.

Increases in parental stress and mental health problems

Economic pressures can also have an impact on parents’ mental health. The mental health of mothers (there is currently no equivalent data on fathers) has been shown to be a key factor in the relationship between economic hardship and play activities, discipline and how the mother feels towards the child.

The pandemic has negatively affected parental mental health and increased inter-parental conflict at a time when parents have less access to support. Over 70% of parents of young children report that being a parent is stressful and that they feel judged as a parent by others. Not all parents receive the support they would like and many face barriers to accessing help. Close to one fifth (18%) of parents of young children have two or fewer people they can turn to locally for help.

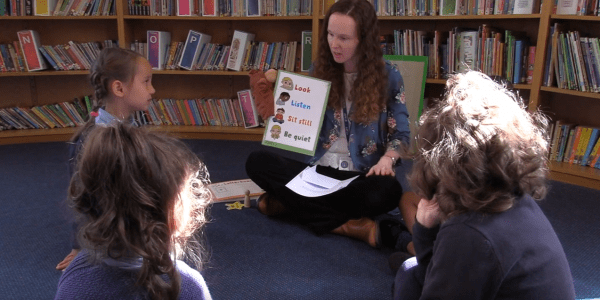

Do parenting programmes help support parents and children?

Parenting programmes can support parents by helping to improve parenting skills and improving the home learning environment. A number of programmes have been shown to improve outcomes for children and parents across a range of different areas of parenting and development. But evidence is limited about which programmes can work well for different groups of parents and some groups of families are underserved by programmes designed to support them. In addition, parenting policy has been patchy. However, the government’s recent initiatives to create Family Hubs and the Best Start for Life are an important step forward.

Over the last 20 years, there has been a growing variation in family living arrangements and a diversity of family structures. To meet the diverse needs of different families, and in a context of reduced budgets, developing the evidence base for more digital and accessible interventions to support parents is a particular priority.

However, efforts to improve parenting skills are less likely to succeed if not combined with efforts to reduce pressure on families, such as through improving household incomes. The research evidence shows that children who experience poverty and strong parenting skills can achieve good outcomes at age five. To close the disadvantage gap and improve children’s outcomes, policies are needed to both reduce pressures on families and improve parenting skills, using universal and targeted support.

Carey Oppenheim, Early Childhood Lead at the Nuffield Foundation and co-author of the report said:

“Parenting matters. Government initiatives to create a network of family hubs, Best Start for Life and investment in parenting programmes are important steps in the right direction. However, parenting programmes form only one component of the support parents need. The COVID-19 crisis and the cost of living crisis have made it even more crucial that families with young children are also given more fundamental support, in terms of improved access to mental health services, boosted family incomes and improvements to the physical environments in which children are raised.”