16/08/21

5 min read

With children’s social care services currently under review, Harriet Waldegrave draws on her experience as a social worker and the work of the Children’s Commissioner for England to make the case for a consistent offer of early help for families.

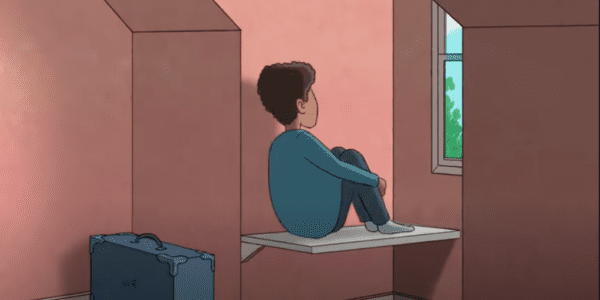

When I was a social worker I often worried just how reassuring the words ‘I’m from children’s services and I’m here to help’ were to the very anxious parent who answered the door.

And I worried about whether I was at the right door, and whether I really could help.

Babies and infants are utterly dependent on the care they get at home. We know that the kind of stimulation and interactions young children have, or don’t have, with their parents can lay the groundwork for their development. They are also the most at risk of being seriously harmed or killed. It is therefore vital that we know which children, in which families, need that extra help, and how to get it to them.

But the youngest children are also often the hardest to identify when they have a problem. Young children are not yet in school every day. The deeply confusing and siloed early years system means it is very hard to be confident that all children who have additional needs are being spotted.

Our research at the Children’s Commissioner’s office found, for example, that although the two and a half year check delivered by Health Visitors is a universal offer, one in five children don’t receive it. Only a third of local authorities know whether the children who missed their check are already identified as vulnerable by children’s services (as ‘Children in Need’). Even fewer know if those children are living in poverty. With so many different systems in place, nobody can be confident that no children are falling between the gaps.

Providing help that families actually want

But even once children are identified as in need of help, are we confident that they are getting what they and their families actually need? There is as yet no national shared outcomes framework for children in need. So it is very hard to understand what interventions have been put in place, how long for, and what happened as a result.

When I think of the families I worked with, even those that were eager for help and knew they were struggling, often became frustrated with how little social services could do for them – whether that was helping them to access the mental health support they might need as a parent, practical help with their housing, or support for a child’s additional learning needs. All of these were different systems, with competing demands, which didn’t join up. Even the most dedicated and skilled social workers that I was lucky enough to work alongside faced frustration at the limitations of what they could do. In particular, their high caseloads often forcing them to focus on the most at risk children. Too often ‘help’ translated into an hour long visit every four weeks, without the time to build real relationships and genuinely understand what was needed.

I think the Independent Review of Children’s Social Care is absolutely right that we need to take a step back and work out how we can provide help that families actually want. We must do more to ensure that a Child in Need plan genuinely fulfils the intention of the Children Act 1989, to not only safeguard but also ‘promote the welfare’ of a child.

Reforming children’s social care

There are some exciting acknowledgements from government that a change of some kind is needed. We have now had the Leadsom review which talks about an offer of support in every local area, with both a Universal and a Universal+ offer, to families who might need more help in the first two years of a child’s life. Given the reduction in funding for early intervention services over the years, and the very variable numbers of children health visitors are responsible for in each area (our report found this ranged from under 50 to over 800), these plans will require an injection of funding.

Likewise, there is the manifesto commitment towards delivering Family Hubs, to work in tandem with the ‘Troubled Families’ programme (thankfully recently renamed to the ‘Supporting Families’ programme). Again, not only will these need a long-term funding commitment at this year’s Spending Review, but a clear vision for how Family Hubs and the Supporting Families programme can best work with families in the earliest years.

Offering the right intervention at the right time

As we bring about this reform, we need to be careful of getting stuck on a debate about whether the state is intervening too much or too little in families lives. As the Nuffield Foundation Review, Protecting young children at risk of abuse and neglect rightly argues, it is entirely possible for us to be doing both. We have seen the number of child protection investigations rise, with ever more closing without further action taken. Some argue this is a sign of a worryingly risk averse system that needlessly interferes. Yet we also know from analysis of surveys that far more children are living with certain risks – for example experiencing domestic abuse in their home – than come to the attention of children’s services.

When I was a social worker it was a very rare thing to close a case and be confident that the child would not benefit from any additional services. So it is not a question of too much or too little intervention, but whether the right level of intervention is offered at the right time. I believe that there are many more children in England who could benefit from additional help, from a trusted source, who can assess and understand what their needs are, than currently receive it. In addition to significant investment in these ‘early help’ services, there also needs to be a commitment for them to work together, to the same outcomes, and analysis of whether the help that was offered made a difference.

The ‘Big Ask’ survey

The Children’s Commissioner recently completed the ‘Big Ask’ survey, during which we spoke to parents about what they wanted to see in their areas for families with babies. They were clear that the pandemic had taken its toll on their mental health and their children’s development. Parents also needed more help that was less of a postcode lottery. We will be publishing some of our most pressing policy calls as a response to this survey in September 2021. Our focus will be on the need for dedicated funding and a consistent offer of early help for families. We will also be launching our Childhood Commission to consider ways to address some of the deeper, more structural problems facing. We hope to understand how we can make sure no child falls between the gaps, and that they get help from services working together to achieve the same goals.

I hope that we will then see a system when social workers, other professionals and families would always feel confident that when an offer of ‘help’ came from children’s services it would be genuinely welcome.

About the author

Harriet is a Senior Public Affairs and Policy Analyst at the Office of the Children’s Commissioner; this is a statutory body responsible for promoting and protecting the rights of children as set out in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. The office has a particular focus on the most vulnerable children – those who are living away from their families in care, mental health institutions, or youth offending settings and those children who have a social worker. Harriet works across a wide range of policy areas, but with a particular focus on early years policy, domestic abuse and children living in secure settings. Harriet has worked in children’s policy for think tanks and charities, and also spent two years working as a child protection social worker.