25/05/23

4 min read

Principal Research Fellow Dr Vicky Kemp on her ground-breaking research into children’s experiences of the criminal process.

Dr Vicky Kemp from the University of Nottingham is the first researcher to be given access to talk to children about their legal rights while detained in police custody.

Tell us about your Nuffield-funded project

The Foundation funded me to examine the impact of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act (PACE) 1984 on child suspects detained and questioned by the police. I was given access to talk to detained children about their legal rights, the first time this has been allowed in England and Wales.

In total 32 case studies were carried out in three police force areas and, in addition to talking to the child suspects, we conducted research interviews with those involved in the questioning of child suspects and listened to recordings of police interviews.

Further analysis of electronic custody data from eight police forces gave us a broader national picture. Through these diverse perspectives, and particularly the experience of police custody from a child’s viewpoint, we concluded that children are processed through a punitive and adult-centred system of justice.

Our recommendations for change set out a comprehensive set of measures designed to achieve a ‘Child First’ approach in police custody.

What were the origins of the project?

My previous experience as a paralegal, providing police station legal advice in the 1980s, including to child suspects, was the inspiration for this project. Having subsequently undertaken a number of empirical studies in police custody as a senior researcher, I was keen to engage with children when detained. Because there are long delays associated with getting consent from Appropriate Adults to engage with child suspects, we obtained ethics approval to approach a child in detention without the consent of an adult if they were not available, although subject to rigorous safeguarding and informed consent protocols.

Why does this research matter?

This project matters because for the first time in almost 40 years since PACE was first implemented, we have been able to view the criminal process through the eyes of a child.

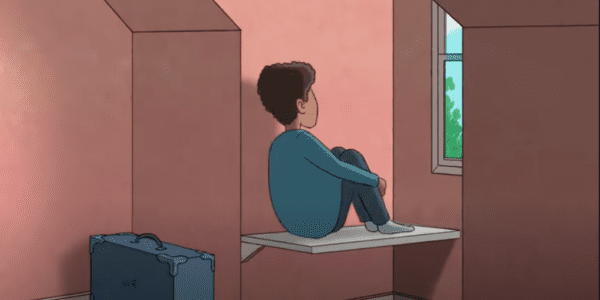

From the child’s perspective, the findings are shocking, particularly when listening to many children’s experiences of having to wait for many hours in a cell, with little or no distractions, not knowing what was happening, and not understanding their legal rights.

PACE safeguards make it mandatory for an Appropriate Adult to be involved when dealing with a child suspect, but for various reasons these adults tend not to have contact with a child until the time of the police interview, which is often many hours after their detention.

The research also shows how the police are left alone to deal with children who come into contact with the law. With no access to children’s services, particularly at night, children can be detained in custody as a ‘place of safety’, but this draws them into an adversarial process.

Being held in custody is a harsh and punitive experience for many children, which fosters resentment and undermines trust in the police. It is the antithesis of the ‘Child First’ approach that is to be found within the wider youth justice system.

Being held in custody is a harsh and punitive experience for many children, which fosters resentment and undermines trust in the police.

What motivates your research interests?

I want to challenge the punitive and adult-centred processes that operate in the early stages of an adversarial system of youth justice. From observing and talking to children in police custody, it is apparent that criminal processes are prioritised over their needs.

In some cases, for example, a child detained as a suspect is later identified as the victim in the case but remain in detention, with the police priority being to interview them. There are other cases where a child is brought into custody following an argument at home, and with the police unable to contact social services, they are drawn into the adversarial process because custody was seen to be a place of safety.

My motivation is to use children’s experiences to challenge such inappropriate practices and instead to require the ‘Child First’ approach found elsewhere in the youth justice system to be adopted in police custody.

What would you change within youth justice if you had the power and resources?

I would increase the minimum age of criminal responsibility to at least 14 and restrict older children being drawn into an adversarial system of justice unless they were being dealt with for a very serious offence. Instead, they should be an increase in the use of diversion, minimum intervention, problem-solving and restorative approaches when dealing with children who come into conflict with the law.

What’s been your experience of being funded by the Nuffield Foundation?

My experience has been extremely positive. At the beginning we had some difficulties in conducting the interviews in police custody due to the pandemic. It would not have been surprising if Nuffield had withdrawn the funding but they didn’t and we were able to continue with this important project.

We have also found the Foundation to be flexible when recognising the difficulties and delays researchers can experience when seeking to access sensitive data on people held in police custody. Agreeing to an extension to this project allowed us to analyse and present findings on over 50,000 electronic custody records drawn from eight police force areas. This element of the research is particularly important because it means we can demonstrate to the government the importance of electronic custody record data in providing strategic oversight of PACE safeguards.

What are you most proud of having achieved in your professional life to date?

With funding from the Nuffield Foundation, I am most proud that for the first time in England and Wales, I’ve been able to talk to children held in police custody about their legal rights. I hope that reporting their experiences will provide the impetus for reforming these early stages of the criminal process.

Read more about the project

The Nuffield Foundation is an independent funder. The views expressed by Nuffield-funded grant holders are not necessarily those of the Foundation itself.